The British Library, piazza, boundary wall and railings to Ossulston Street, Euston Road and Midland Road

Listed on the National Heritage List for England. Search over 400,000 listed places

Overview

- Heritage Category:

- Listed Building

- Grade:

- I

- List Entry Number:

- 1426345

- Date first listed:

- 31-Jul-2015

- List Entry Name:

- The British Library, piazza, boundary wall and railings to Ossulston Street, Euston Road and Midland Road

Location

Location of this list entry and nearby places that are also listed. Use our map search to find more listed places.

Use of this mapping is subject to terms and conditions.

This map is for quick reference purposes only and may not be to scale.

What is the National Heritage List for England?

The National Heritage List for England is a unique register of our country's most significant historic buildings and sites. The places on the list are protected by law and most are not open to the public.

The list includes:

🏠 Buildings

🏰 Scheduled monuments

🌳 Parks and gardens

⚔️ Battlefields

⚓ Shipwrecks

Historic England Archive

Search over 1 million photographs and drawings from the 1850s to the present day using our images archive.

Find PhotosOfficial list entry

- Heritage Category:

- Listed Building

- Grade:

- I

- List Entry Number:

- 1426345

- Date first listed:

- 31-Jul-2015

- List Entry Name:

- The British Library, piazza, boundary wall and railings to Ossulston Street, Euston Road and Midland Road

- Location Description:

- The British Library, 96 Euston Rd, London NW1 2DB

The scope of legal protection for listed buildings

This List entry helps identify the building designated at this address for its special architectural or historic interest.

Unless the List entry states otherwise, it includes both the structure itself and any object or structure fixed to it (whether inside or outside) as well as any object or structure within the curtilage of the building.

For these purposes, to be included within the curtilage of the building, the object or structure must have formed part of the land since before 1st July 1948.

The scope of legal protection for listed buildings

This List entry helps identify the building designated at this address for its special architectural or historic interest.

Unless the List entry states otherwise, it includes both the structure itself and any object or structure fixed to it (whether inside or outside) as well as any object or structure within the curtilage of the building.

For these purposes, to be included within the curtilage of the building, the object or structure must have formed part of the land since before 1st July 1948.

Location

The building or site itself may lie within the boundary of more than one authority.

- County:

- Greater London Authority

- District:

- Camden (London Borough)

- Parish:

- Non Civil Parish

- National Grid Reference:

- TQ2997082897

Summary

Public Library, the present design based on that of 1975-8, built 1982-99, though opened in 1997; architect Sir Colin St John Wilson, with M.J. Long, Douglas Lanham, John Collier, John Honer and many more.

Reasons for Designation

The British Library designed by Sir Colin St John Wilson with M.J. Long, built 1982-99, is listed at Grade I for the following principal reasons: * Architectural interest: for its stately yet accessible modernist design rooted in the English Free tradition with Arts and Crafts and classical influences, crisply and eloquently contextualised by its massing and use of materials which respect and contrast to the St Pancras station and hotel; * Materials: for its level of craftsmanship and skilful handling of a range of materials externally and internally, including Travertine, Portland and Purbeck stone, granite, Leicestershire brick, bronze and American white oak throughout, carefully and meticulously detailed; * Interior: for the well-planned interior spaces comprising the generously lit reading rooms and multi-level atrium, successfully fulfilling the brief to create the nation’s Library; * Historic Interest: in the tradition of the Royal Festival Hall, it is a landmark public building incorporating at its heart the King’s Library, given to the nation by George III; * Architect: a major work by the eminent architect and academic Sir Colin St John Wilson and his architectural partner, M.J. Long. Wilson has a number of listed buildings to his name notably the St Cross libraries at the University of Oxford (Grade II*); * Artistic interest: for the fusion of art with architecture as a component of the design ethos, exemplified by Paolozzi’s Newton in the piazza; * Group Value: with the Grade I St Pancras Hotel, Grade II Camden Town Hall and Grade II housing on Ossulston Street.

History

The British Library has a long and complex history before it was even imagined on its current site. In 1757 George II presented the Royal Library of 10,500 volumes collected by British monarchs from Henry VIII to Charles II, a gift which brought with it the privilege of receiving a copy of every book registered at Stationers’ Hall. Further donations of manuscripts and state papers followed including the gift of George III’s books by George IV, and the building of the King’s Library was the first phase of the British Museum built in Great Russell Street in 1823-6. In 1852-7 the courtyard of Sir Robert Smirke’s building was infilled by a new Reading Room, designed by his brother Sydney. In 1911 the Copyright Act granted the Library a copy of every book, periodical or newspaper published in Britain. The Newspaper Library had been built at Colindale in 1904-5; in 1914 the Edward VII galleries were opened and in 1937 the North Library was constructed within them. The congestion was intense and delays in waiting for books notorious.

The 1943 'County of London Plan' suggested the opening up of land south of the British Museum in Bloomsbury to form an open space and provision for new library facilities, although ideas of opening up a vista from the British Museum go back much further, for example to W. R. Lethaby’s idea of the ‘Sacred Way’ linking it to Waterloo Bridge made in 1891. In 1962 Sir Leslie Martin and Colin St John Wilson were among a number of architects invited to compete by interview for the project, just as they were completing the St Cross group of libraries for Oxford University. These were three libraries, reached at different levels off an external staircase that forms the centrepiece of the design. The small library for the Institute of Statistics has gone, but the English and Law libraries are both square and top lit, with galleries and peripheral carrels. For Leslie Martin evolution was more important than innovation, something he noted that Alvar Aalto had identified in his own library work, and he suggested in his 'Buildings and Ideas', 1933-83, from the Studio of Leslie Martin and his Associates, Cambridge University Press, 1983, that having determined an ideal plan at St Cross, which was repeated for each of the three libraries there, it only needed refinement elsewhere. This idea was developed further by Wilson.

Wilson felt that the success of the St Cross libraries recommended him and Martin to the Ministry of Public Buildings and Works. Nevertheless their first proposals combined the stepped internal courtyard plan of St Cross (and their other university work) within a larger context. The first scheme, approved early in 1964, was an ambitious project that created a piazza south of the British Museum down to Nicholas Hawksmoor’s St George’s, Bloomsbury. To the east would be a new library for books, maps, music and manuscripts, while to the west would be a gallery, archives for prints and drawings, and a conference centre. There would also be a residential development, with shops, publishers’ offices and a public house.

Elements of Martin and Wilson’s St Cross scheme can be seen in the eastern block of the proposal, and of the practice’s Harvey Court, Cambridge, in the western, but on a scale and grandeur that was unprecedented, and with a basement archive going down some seven storeys under the piazza. Then a new Labour Government asked for a scheme that would also include the Science and Patents departments as well as the Library’s humanities collections. The desire for a doubling of the library accommodation coincided with growing conservation pressure, always sensitive in Bloomsbury, which demanded the retention of properties on Bloomsbury Square and a consequent reduction in the size of the development site. Martin withdrew in 1970. In 1972 Wilson produced a dense scheme for a large new British Library - a square, stepped block for the main collections and a long wing for the Science Collections, together with a residential precinct of stepped terraces running eastwards from St George’s Bloomsbury. Recognising the scale of what was required, in 1973 the Government instead purchased nine acres of the St Pancras Goods Yard then being vacated by British Rail, and Wilson set to work on a new scheme in 1975. The brief was now to serve an independent British Library, formed by the British Library Act of 1972 that brought together the British Museum Library, the National Central Library and the National Lending Library for Science and Technology. In 1980 a small extension by Wilson to the British Museum on Museum Street was opened.

The BL site is a wedge-shaped piece of land bounded by Euston Road to the south, by Midland Road to the east and by Ossulston Street to the west. Wilson’s designs, which rapidly gained approval in 1978, retained the idea of placing the Science and Patent collections in a long wing, which with conference facilities and staff offices lines Midland Road. A series of square, top-lit libraries with galleries, serve the remaining collections, with a large general reading room, and specialised libraries for studying rare books, music and maps. Between the two areas was planned a vast Reference Reading Room an entrance hall, and a new piazza on to the Euston Road. Wilson’s aim was to create an environment that was ‘vivid, pleasurable and memorable, while fitting with responsibility and sensitivity into its context’. The RIBA Journal for April 1978 (from which that quotation is taken) estimated that it would take twenty years to build. The Bloomsbury scheme was described as ‘monumental’ and ‘classical’, that at St Pancras ‘a contemporary, stripped vernacular look’ (Building Design, 10 March 1978) yet within the context of Wilson’s whole body of work the similarities are greater than the differences, and show the evolution of his designs in the manner Martin and Aalto considered so important.

In 1978 the decision was made to build the design in three phases. Work began in 1982, when Princes Charles laid the foundation stone, but following extensive tests to the foundations the main building campaign began in 1984. The engineers, Ove Arup and Partners, faced a monumental task in constructing such a deep basement area out of the London clay so near major London Underground tunnels and next to the Grade I-listed St Pancras Station and Hotel. Phase 1, representing c 60% of the whole project, was sub-divided into three for the purposes of measuring annual expenditure targets. Phase 1a provided an equivalent space to that existing in Bloomsbury, with Phases 1b and 1c allowing for moderate expansion. The existing building is essentially a reduced version of phase 1 - following a decision made in December 1987 to complete the building to this reduced scale, leaving the scheme with scarcely more seats than had the old Reading room in Bloomsbury. Wilson commented that ‘it was like constantly pulling a plant up by the roots to see if it was still alive and then cutting a bit off before shoving it back in the ground’ (Stonehouse, 2007, 111). The design as built was more sophisticated than the original. The Humanities and specialist reading rooms were already grouped in two square, top-lit areas (making for a larger entrance courtyard than in the 1978 design) and the Science collections given their separate wing. In 1986-7 Wilson replaced the original Reference Reading Room with a central glazed casket or shrine, the King’s Library - likened by him to the Kaaba at Mecca but also with similarities to the Beinecke Rare Book Library at Yale University in New Haven by Gordon Bunshaft of SOM, and placed comprehensive café facilities behind it. A library for the India Office collection and exhibition areas were designed at this stage. To the rear, the north elevation was designed to allow for future extension. The principal works of art, including Eduardo Paolozzi’s Newton (1995) after William Blake and a tapestry based on R. B. Kitaj’s If Not, Not, were commissioned at this time. The leather reader chairs were specially designed by Ron Carter.

It was also in 1990 that the National Audit Office complained that it was the very decision to phase the work that had cost so much time and money, made worse by the subsequent sub-division of that phasing, and the stop-go funding of the project throughout the 1980s. The project was split between the Office of Arts and Libraries and the Property Services Agency - in fact the only people not to be criticised by the National Audit Commission were Wilson and his design team, who provided the only continuity through the project.

Sir Colin St John Wilson (1922-2007), Professor of Architecture at Cambridge University between 1975 and 1989, began his career at London County Council where he collaborated with (Sir) Leslie Martin, among many others, before becoming a lecturer in Architecture at Cambridge in 1956 where Martin was Professor. Wilson and Martin worked together on a number of projects, but Wilson is undoubtedly best known for his design of the British Library, a project of some 30 years duration. A highly influential architect of the post-war period, his renown is attested by 10 of his buildings being designated, including the Oxford University St Cross Library building (1961-5) and Harvey Court halls of residence at Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge (1961-2) both listed at Grade II*. Wilson's principal architect partner was M.J Long (b.1939). M.J. Long studied at Smith College in Massachusetts, and received her MArch from Yale in 1939. She worked for Sir Colin St John Wilson from 1965 to 1996, as a partner from 1974, and latterly a director. She also ran a separate practice (MJ Long architect) from 1974 to 1996.

ALTERATIONS: there have been a number of minor alterations to the Library’s fabric, primarily to adapt the facilities to changing needs of the public and to comply with the Disability Discrimination Act (DDA) provisions. These include:

- External installation of DDA-compliant ramps and handrails, bollards to external entrances and lighting to the Newton statue and clock tower;

- Reading Rooms: altering reading room counters; installing electronic resource desks in the Rare Books Reading Room; converting a shelved storage area on the Lower Ground floor and installing a glass partition in Science 1 Reading Room;

- Public realm: installation of automated door openers in public areas to improve access;

- Conference Centre: refurbished in 2010, including the recovering of the auditorium seating.

In addition, the British Library have carried out ongoing maintenance and upgrading of office spaces, lifts, lighting, CCTV, fire alarms and access controls.

Details

Public Library, the present design based on that of 1975-8, built 1982-99, though opened in 1997; architect (Sir) Colin St John Wilson, with M.J.Long, Douglas Lanham, John Collier, John Honer and many more. The structural engineers were Ove Arup and Partners, with mechanical engineering services from Steensen Varming and Mulcahy and quantity surveyors Davis Langdon and Everest. William Lam advised on lighting.

The Conservation Centre: although attached to the rear north elevation (Long and Kentish, 2006), the centre is a separate building and very recent in date. It is not part of the special interest of the Library.

Works of art: some significant internal and external works of art associated with the design of the library, contemporary with its completion and opening, and supported by outside sponsorship are of special interest and included in the listing. Where this is the case, these are specifically mentioned in the List entry. Other free-standing or ‘curated’ works are not included.

STRUCTURE AND MATERIALS

The building has a concrete frame, based on 7.8m x 7.8m column centres, clad inside and out in red brick (hand-made, sand-faced dark Victorian Reds from Leicestershire) laid in stretcher bond, chosen because they were made of the same clay as those used for the adjoining St Pancras Station and Hotel immediately to the east. In a contrasting red to the brick there are metal sills and cornice bands, and cladding to the columns, the latter with stylized classical motifs, and dark green metal fascias to the science rooms, colours inspired by the adjacent St Pancras Station and Hotel. Special stainless steel wall ties allow vertical movement between the series of sub-frames and the brick skin. There is a granite plinth to the Midland Road elevation, with plaster and panelling contrasted with brick and tile within; external columns are clad in steel. The stepped roofs are slate-covered, again akin to St Pancras Hotel, contrasting with the steel screens shielding the clerestory glazing. The brick and stone paviours to the forecourt are continued within the building.

Interior joinery throughout is in American White Oak, with maple used only in the Conference Centre. The floor and wall finishes are of Travertine, Portland Whitbed, and Purbeck limestone, with contrasting Travertine and brick paviours on the ground floor of the atrium. In general the door furniture and stair handrails are in brass, the latter over bound with leather, with a bronze structure to the King’s Library.

PLAN

The building comprises two main blocks of libraries above ground, linked by a central entrance range, with a large piazza over four tiers of basement stacks on piled foundations, and small additions to the rear. The basement is divided by the tunnels of the Northern and Victoria Lines, with resilient bearings separating the conference centre structure from the Hammersmith and City/Circle Lines. The frontage parallel to Euston Road contains the main entrance and atrium, with the King’s Library and restaurants behind; to the west (left) are the humanities, rare books and music libraries; to the east (right) the science and patent libraries adjoin the conference centre (with its own entrance) parallel to Midland Road, making an acute angle, with a vertical clock tower containing service shafts between the west block and entrance range. Additional public and staff entrances are along Midland Road.

EXTERIOR

The south elevation facing the piazza includes the main ENTRANCE. Steps lead to the sliding entrance doors, set at grade under a canopy with a display window to the gift shop to the left; the ramp to the right of the steps was constructed in 2014. To the left (west) of the entrance, each panel of the five-bay, four-storey frontage (housing internally the exhibition rooms and shop), has two metal roundels, above which is an additional step and clerestory to the roof. The western block is itself divided into two six-bay blocks, each of six bays, to the west with double-stepped pitched roofs, and a flat roof to the raised set-back block in between.

A ten-bay block to the east (right) rises to six main storeys with staff facilities behind, its height determined in relation to the hotel and station across the road to the east; panels of brushed metal sun shields are repeated on the east and west elevations. The CLOCK TOWER rises above the junction between the east block and the stepped roofscape of the entrance. The clock near to the apex faces south with stepped brick and red metal detailing above. Feature spotlighting added to the base of the clock tower in 2014 is not of special interest.

The CONFERENCE CENTRE adjoins seamlessly to the south, its entrance at the forecourt elevation, with a large porthole opening above to light the stairs within, and its raked pent roof-line presenting a bold face to Euston Road, broken by two bands of projecting triple-glazed fenestration with sun screens at the south-east corner. To Euston Road, a modest kiosk café and an undercover ramp (added in 2010) that leads through to the piazza are not of special interest. On the Midland Road elevation a colonnade, with metal railings in between, rises from a Royken granite plinth and supports the projecting and stepped east wing above with long strip windows defined by louvred metal sun screens and interrupted by a projecting ‘V’-shaped staircase ‘oriel’ window; the soffit is coffered. The north elevation has landscaped roof terraces incorporating a circular pergola and a projecting stair tower.

The rear (north) elevation was intended by Wilson to allow for further phases of building (see history above). It has a series of stepped terraces repeating the same idiom of brick panels and paviours, with planters and a square-patterned trellis and balustrade somewhat reminiscent of Frank Lloyd Wright. There is a broad public terrace with planting boxes leading out from the large staff restaurant, which has a fully-glazed facade shielded by metal screens; above it is an enclosed terrace, including a circular pergola surrounding fixed wooden seating.

The west elevation (to Ossulston Street) and rear elevation of the western block is supported on red columns with deep bracketed eaves and has a stepped roof; an external circular escape stair for the humanities reading room, constructed with radial bricks, is attached to the rear.

Despite the contrast of square and diagonal, the structure of the two blocks is on a strong square grid, reminiscent of that which governs Wilson’s nos. 2 and 2a Granchester Road, Cambridge (a pair of houses of 1961-64, one of which with a studio for himself, listed at Grade II, NHLE ref 1392069), and which appears in details such as coffering, doors and screens, the supports of the uplighters, glazing, grilles and trellises. Common ingredients are set out in Stonehouse (2007).

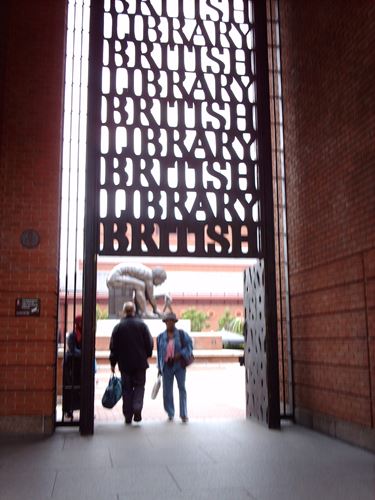

PIAZZA, PORTICO AND EXTERNAL ARTWORKS

To the south (front) of the main entrance is a forecourt known as the piazza with brick paviours set within a grid of limestone slabs that includes steps, raised levels and a rotunda defined by walls topped with granite boulders at the entrances; Sir Antony Gormley’s ‘Planets’ installation of 2002, noted but at the time of the inspection (2015) but is not part of the special interest of the building. There are flag poles and a temporary, free-standing café on the piazza; neither the café here* nor other cafes* within the building’s envelope, or the flagpoles* are included in the listing. DDA compliant handrails have been added in a number of places and are not of special interest. A raised plinth at the point of intersection between the main south and angled, ramped south-eastern entrance incorporates Eduardo Paolozzi’s Newton (after Blake), installed in 1995, an integral part of Wilson’s composition and made by the Morris Singer Foundry with raised planting behind. Feature lighting for Newton, with an associated plinth made by East Coast Casting, was added in 2014 and is not part of the special interest of the building. To the south on the Euston Road entrance, the square brick entrance gateway, known as the Portico, forms a rectangular frame to an angled entrance, with a stone panel incised with the name ‘The British Library’ repeated in the pattern of the iron gates and their high overthrow, by David Kindersley and Lida Cardozo. The bronze chair, Witness, by Sir Antony Gormley, installed in 2011, is noted but is not part of the special interest of the building.

INTERIOR

The interior of the Library combines quiet, top-lit reading rooms in the west and east blocks joined centrally by a complex space of multiple entrance concourses arranged in terraces organised with the King’s Library at the core.

Freestanding furniture throughout is noted because it was designed by the architects (with Reading Room chairs by Ron Carter) but cannot be included in the listing. Fixed furniture is included in the listing unless stated otherwise.

Interior artworks: the British Library retains numerous works of art as part of their collections, some of which are displayed within the building. However, for ease of their curation, and in recognition that they may be donated items, these works of art* are not included in the listing, although purpose-built architectural elements for housing them may be included and will be specified.

PUBLIC REALM

Entrance and catering areas: bronze sliding and double entrance doors lead to a low vestibule with shop and exhibition halls to the west (left), from which stairs rise to an atrium on four main levels with galleries reached off dog-leg stairs to left, a ramp and a more dramatic spiral stair to right, set behind stairs to the lower ground and a low fountain. Travertine columns contrast with Portland limestone floors in two colours; internal porthole openings light the spaces to the right. The cyma curve roof incorporates clerestory glazing with top lighting to the rear and inset spots; the hanging lights are by Juha Leviska. The central control desk divides access to this main space into two. The main foyer at ground level is defined by built-in seating and balustrading of travertine, with plant troughs. A bronze chair* by Gormley, was installed on the ground floor c.2012 but is not part of the special interest of the building.

The lower ground floor has travertine columns, beams, dado and lift surrounds (as repeated in the rest of the building), limestone and brick paviour floors. The cloakroom has a sinuous counter * and banks of oak lockers* are attached to the walls; these are not included in the listing. Access to offices lie through double doors to the left. Fixed sculptures integral with the building are Anne Frank by Doreen Kern was installed in this location in 2003 and is not of special interest. Paradoxymoron is a painting of 1996 by Patrick Hughes. The reconfigured education space* on this floor is not included in the listing.

To the centre of the ground floor are sets of escalators next to the stairs of limestone with Travertine balustrades leading to the Upper Ground Level and Level 1; handrails – like the door handles – here and through the building are wrapped in leather with brass curves, inspired by those of Gunnar Asplund and Alvar Aalto. In the lift lobby at Upper Ground Level is a model * of the Library set on a plinth*, cut to reveal the basement stacks below the piazza, which is not included in the listing.

There is much art on display in the entrance atrium. A wall tapestry, conceived as part of Wilson’s original design, based on R. B. Kitaj’s If Not, Not, made by Edinburgh Weavers was moved to the side of the front entrance in 2013. A statue of Shakespeare* (a replica based on that by Roubiliac 1758) stands to the left of the stairs to the west wing above a stepped, inscribed plinth marking the opening of the Library by Queen Elizabeth II on 25 June 1998. On the west wall of the atrium, four busts* in red steel roundels of the donors to the collections (Sir Thomas Grenville, Joesph Banks, Sir Robert Cotton and Sir Hans Sloane) are also replicas. The statue of Shakespeare* and busts of the donors* are noted because of their prominence in the atrium but are replicas and are not included in the listing although their architectural plinths are included.

Banks of lifts serve the two sets of reading rooms either side of the atrium, the lobbies of which have travertine detailing and limestone borders to the carpeted floors. All carpet* is of standard contract range and not included in the listing. All lifts* in the library are utilitarian and are not included in the listing. Other balustrading is formed of simple steel uprights with a brass top rail. There is built-in bench seating within travertine walls, and black fossil limestone paving to the rear gallery serving the cafe at Upper Ground Level, with kitchen and staff restaurants behind on Level 1, separated by oak doors and louvres. The fixtures* and fittings* of all catering areas, restaurants and lounges for both public and staff use, including seating*, counters*, vending equipment and kitchen equipment*, are not included in the listing.

A belvedere at Level 1 gives views across the foyer. Two more floors above this level have walkways and balconies at the rear over the entrance to the servery. A corridor, with a built-in travertine seat, leads to the staff restaurant and outside terraces for staff and public, including the pergola garden. Limestone floors also serve the lower restaurant area, the stair to which has a built-in travertine handrail and inset lights; there are travertine stall risers to the servery.

Exhibitions: at the Upper Ground floor of the western range, beneath the Rare Books Library, is the Sir John Ritblat Gallery, a permanent display of the ‘Treasures of the British Library’, with a central service core and concrete columns with afromosia veneer coating. Here there is a combination of free standing temporary cases which not of special interest and, attached to the enclosing walls, permanent cases contemporary with the building. Stairs lead down to the Paccar Gallery for temporary exhibitions, which partly underlies the ‘Treasures’ exhibition, with access points from both the Ground and Lower Ground floors; the wall partitions in the Paccar exhibition and the stairs between the Paccar and Treasures exhibition spaces* are functional and do not form part of the listing. The adjacent exhibition workshops* are classed as office areas and are not included in the listing. Stairs with travertine risers and steel and brass handrails lead down from the ground floor to the Paccar Exhibition space but beyond this point the exhibition partition walls*, fixtures* and fittings* are temporary, not fixed and not included in the listing. At the Upper Ground floor, to the rear of the foyer, is a temporary exhibition area, again with free standing fittings, masking the view of the King’s Library at this point; the exhibition panels* and structure* are not included in the listing because of their temporary nature.

Shop and Box office: flanking each side of the atrium’s ground floor, both the shop* and box office* have C21 shop fronts* and fittings* and are not included in the listing.

Reader Registration* is a remodelled office area at Upper Ground level which is not included in the listing. Toilets* for staff and public throughout the building are utilitarian and are not included in the listing.

READING ROOMS AND THE KING'S LIBRARY

There are 11 reading rooms in total, divided broadly into humanities on Levels 1 to 3 in the west block, fronting Ossulston Road, and science in the east block on Levels 1 to 3, fronting Midland Road.

King’s Library: rising in the centre of the building behind the foyer, the King’s Library is accessed from a bridge over a narrow ‘moat’ at the Upper Ground floor through heavy bronze double doors. It is a six-storey glazed casket, served by an internal lift and escape stairs, with an independent structure comprising a bronze framed curtain wall set within a trough or moat, travertine walled with a glass balustrade and black marble base. Wilson described it (1998, references below) as ‘an object in its own right … simultaneously a celebration of beautifully bound books, a towering gesture that announces the invisible presence of treasures housed below and a hard-working sources of material studied in presence of treasures houses below and a hard-working source of material studied the Rare Book Reading Room opposite: the symbolic is at one with the use’. The books are placed on outward-facing shelving as close to the glass as is feasible, on stacks which move inwards while allowing air movement for the preservation of the books, so that the bindings can be enjoyed. Subtle lighting within alternate mullions inside the cases highlights the bindings. At the centre are fixed stacks. There is a bust of George III* by Peter Turnerelli,1812 on a black marble plinth, of note, but not included in the listing.

Humanities Reading Room: access to the Humanities Reading Room is at level 1 in the west block. This lofty, triple-height and essentially square space, receives generous daylight through rooflights and clerestories with a coved ceiling sweeping up to the top-floor clerestory. Inserted on two sides are the two projecting and stepped upper floors, enclosed by giant square piers accessed by internal timber-lined stairs; the third being the map room. The piers are panelled to shoulder height in American White Oak incised with delicate lines, imitating fluting; all timber detailing used for the balustrades, desks and wall shelving and joinery is American White Oak. The pierced oak balustrading to the upper floors has elongated stanchions, repeated as a vertical motif in the cornice that makes a feature of the air ducts and lighting troughs below, and countered by the multiple vertical shafts of the up-lighters; the built-in oak desks have square patterns incorporating lights and sockets, and brushed black steel built-in lights. Other finishes are in impact-resistant, glass reinforced gypsum (GRG) rather than plaster, for ease of maintenance, plain or sparely detailed with stylized classical motifs with Japanese overtones. All these square and vertical patterns have sources in Frank Lloyd Wright, whose Robie House Wilson particularly admired. This plan form derives from that of Leslie Martin’s Law Library at St Cross, Oxford, designed in association with Wilson and built in 1959-63. The Control and issue desks match the American White Oak panelling and shelving of the walls, and like the desks and chairs are by the architects. The chairs are not fixed, thus are ineligible for listing, but the reading desks, with leather tops, mostly are; some are modified for DDA compliance, others altered to take computer processor units with additional electrical supply for lap-tops.

Adjacent to Humanities is the Rare Books and Music Reading Room, with the Manuscript Reading Room on the single balcony above. The details here are repeated on a more modest scale, with conoid-topped columns and flatter slopes to the ceiling. Carrels or sound booths against the perimeter wall are built in to the music library, originally, it is said to accommodate those wishing to use portable type writers; the film reader room is alongside. Doors throughout the reading rooms are of American White Oak with brass and bound leather handles, glazed to the booths and film-reader room.

Science Reading Rooms: the eastern block housing the science and social science collections is on three floors, topped by a coffered ceiling that is upswept to the top of the main windows, with a balustrade protecting the ducting below. On the other side are two stepped back galleries with broad timber ledges topped by brass handrails. To the street (Midland Road) it has large, continuous side windows, with in between carrels, desks and a connecting stair with glass balustrades. There are more bookcases for material on open shelves than is found in the humanities libraries; those in freestanding, moveable units* are not included in the listing. There are broad timber ledges to the balconies. Control and issue desks match the oak panelling and shelving of the walls, and like the tables and chairs (not fixed, and the same as those in the humanities reading rooms and not included in the listing) are designed by the architects. Some additional internal glass partitioning was added in 2012 and is not of special interest.

Business and IP Centre: on Level 1 of the east block, formerly a science reading room, the Business and IP Centre has a modernised entrance foyer and inserted glass meeting rooms; the foyer and meeting room partitions* are not included in the listing. The high windows are over-built in shelving and a single gallery whose balustrade is lined in timber (former Science North reading room), linked by a spiral stair (also with a timber balustrade) and with shelving on both levels. Ducts form a cornice, the square columns are timber lined to dado height, and there are built-in desks, not all with reading lamps; the wall shelving is lit with downlights.

Newsroom: on Level 2 in the east block, the newsroom created from a former science reading room in 2014, has a reconfigured foyer* and renewed fixtures* and fittings* and a digital screen* installed. It is not included in the listing.

Asian and African Studies Reading Room: on Level 3 in the east block, formerly the Indian Office Library, is a double-height space so that the historic picture collection can be hung. The fittings are similar to those in the other Reading Rooms.

OFFICES AND BASEMENT

The staff offices are located to the rear of the east and central blocks, the principal entrance being the staff entrance gate (gate 8) from Midland Road. The offices* are adaptable spaces with standard furniture*, fixtures* and fittings* and are not included in the listing with the exception of the 4th Floor Executive office which is included in the listing as a representative example.

Access to the reading rooms and public realm is via stairs to the rear and lifts; there are no notable fixtures and fittings here except for the carved, timber war memorial to all Library Association librarians from the Commonwealth lost in the First and Second World Wars which is fixed to the wall opposite the main lifts to the science reading rooms and is included in the listing. At the rear also is the staff restaurant with timber dado repeated in the maple battens fixed to the bases of circular columns and hanging lights by Louis Poulsen. On Level 4 of the east block is the Board room and its adjacent Executive Office suite, a ‘staff’ area with meticulous travertine and American White Oak finishes; the Board room furniture is by Ron Carter and where fixed is included in the listing.

Beneath the piazza are four vast basement floors* with overpainted brick walls, mechanical and motorised stacking and secure pens for rare and valuable items. On Basement level two is the control room for the Mechanical Book Handling System (MBHS), a bespoke conveyor belt system transporting items in trays to and from the basement to the reading rooms’ service desks via lifts. As part of the integral design of the Library the basements and MBHS are noted here, but none of the basement levels*, their fixtures and fittings* are included in the listing. Collection item storage areas* on other floors, including large areas of the Lower Ground Floor, Manuscripts and Philatelic Storage Rooms are not included in the listing.

Loading bays*, plantrooms*, cores*, lift-shafts*, and other utility and service areas* are not of special interest and are not included in the listing.

CONFERENCE CENTRE

Refurbished in 2010, the centre serves the Library and external functions and is entered from the forecourt through bronze doors, with lower and upper foyers, served by a travertine lined stair well, the treads in Purbeck marble and Portland stone. The lift wall and dado are in travertine with limestone floors and maple joinery. There is a 250-seat auditorium accessed on two levels (seating recovered in 2010) and four seminar rooms seating 20-65 people, of these only the double-height Elliott Room is of special interest; the others have standard fixtures* and fittings*. A large foyer with a bar is reached by a broad travertine-lined stair incorporating built-in seating, and leather-bound brass handrails, dubbed the ‘Spanish Steps’ by Wilson to denote his intention that they be a meeting and conversation place. The toilets* and cloakroom* are not included in the listing.

SUBSIDIARY FEATURES

The entrance adjoins walls to Euston Road and Ossulston Street; the latter has two pairs of set-back gates, the first into the forecourt, the second to the rear of the western wing, and railings set on a low, stone-capped wall with brick piers. The semi-circular planters* to the Euston Road frontage and railings between and including Gate 10 and Gate 9* fronting Midland Road (installed in 2008) are not included in the listing.

* Pursuant to s.1 (5A) of the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990 (‘the Act’) it is declared that these aforementioned features are not of special architectural or historic interest.

This list entry was subject to a Minor Amendment on the 17/08/2016

This List entry has been amended to add sources for War Memorials Online and the War Memorials Register. These sources were not used in the compilation of this List entry but are added here as a guide for further reading, 29 August 2017.

Sources

Books and journals

Cherry, B, Pevsner, N, The Buildings of England: London North, (1998), 372-375

Colin St.John Wilson, Sir , The Design and Construction of the British Library, (1998)

Frampton, , Richardson, , Colin St John Wilson, (1997)

Stonehouse, R, Colin St John Wilson, (2007)

Stonehouse, R, Stromberg, G, The Architecture of the British Library at St Pancras, (2004)

Websites

War Memorials Online, accessed 29 August 2017 from https://www.warmemorialsonline.org.uk/memorial/220512

War Memorials Register, accessed 29 August 2017 from http://www.iwm.org.uk/memorials/item/memorial/11063

Legal

This building is listed under the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990 as amended for its special architectural or historic interest.

Map

This map is for quick reference purposes only and may not be to scale. This copy shows the entry on 22-Apr-2025 at 17:07:52.

Download a full scale map (PDF)© Crown copyright [and database rights] 2025. OS AC0000815036. All rights reserved. Ordnance Survey Licence number 100024900.© British Crown and SeaZone Solutions Limited 2025. All rights reserved. Licence number 102006.006.

End of official list entry